4.1 Methods

4.1.1 Protocol and registration

The literature review protocol was developed by the researcher using the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al. 2018). It was presented to ESS stakeholders at a framing meeting on 26 June 2023 at which the use of the protocol was confirmed. A further milestone meeting was held on 31 July 2023 to review progress.

4.1.2 Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria for individual sources were developed.

- publication date: 2008-2023

- language: English

- type: academic

- publication status: published

The decision to limit the review to sources published since 2008 was made to increase the relevance of sources to current and future approaches to compliance, given the ongoing development of relevant legislation and case law. Sources included in languages other than English were excluded due to capacity and available language skills. The prioritisation of published academic sources, as above, reflected the availability of standardised academic databases, and the capacities of these for developing an efficient and rigorous review, rather than a judgment on the relevance of other sources.

4.1.3 Information sources

Scopus, provided by Elsevier, and the Web of Science, provided by Clarivate Analytics, were selected for use as information sources in the study. Both databases are widely used for the purposes of scoping and systematic academic literature reviews. An initial search using keywords such as ‘Aarhus Convention’ identified a wide range of individual sources in both databases, demonstrating some overlap but also substantively different coverage. An overview of the search process and results, and the steps taken to manage the data is included in the next section.

Scopus contains over 90 million records, and covers over 26,000 peer reviewed journals, 292,000 books, and 148,000 conferences and events (Scopus 2020, 4). Searches in the Web of Science were conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection. This contains over 85 million records, and covers over 21,000 peer-reviewed journals, 300,000 conferences, and 134,000 books in 254 subject categories in the sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities (Clarivate 2023).

The researcher used their access to the University of Glasgow library’s online resources to access the information sources and the underlying source content. There were a number of instances in which the content was not available from the University of Glasgow library’s online resources. In these cases, source content was retrieved using google searches if possible. If not, this functioned as a reason for the exclusion of the source. There are 43 instances in which this occurred.

4.1.4 Search

Given the criteria for selection was that the source should display a substantive focus on policy approaches to compliance with the AC, searches using the title, abstract, and keywords were preferred over full-text search, and limiting the search query to keywords that specifically refer to the AC was deemed appropriate. A more expansive approach to the research question could rely on developing keywords that refer to the individual rights proposed in the AC or to individual measures that have been used to implement those rights.

Based on a review of the abstracts of sources derived from a search in the two databases for the keyword “Aarhus Convention”, the keywords “Aarhus Rights” and “Aarhus Regulation” were also included.

The search queries are included in Table 2. The Web of Science ‘TS’ code refers to a ‘topic’ search, which interrogates the title, keywords, and abstract fields of Web of Science records.

Table 2 – An Overview of the Search Queries

| Information Source |

Search date |

Search query |

Results |

| Scopus |

12 July 2023 |

( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “Aarhus Convention” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “Aarhus Rights” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “Aarhus Regulation” ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2007 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , “English” ) ) |

260

|

| Web of Science Core Collection |

12 July 2023 |

((TS=(“Aarhus Convention”)) OR TS=(“Aarhus Rights”)) OR TS=(“Aarhus Regulation”) and English (Languages) and 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 (Publication Years) |

177

|

Data was extracted from the databases, formatted, merged and deduplicated using the simple, no-code process suggested by Caputo and Kargina (2022). Following the de-duplication process, 312 of the 437 records remained.

4.1.5 Selection of sources of evidence

Individual sources in the search results were selected for inclusion in the scoping literature review if they displayed a substantive focus on approaches to compliance with the AC.

Two phases of selection were conducted: a selection based on title and abstract, and a selection based on title and abstract plus source content. The reporting of the selection of sources of evidence outlines the number of sources included and excluded in each phase and summarises common reasons for the exclusion of sources.

4.1.6 Data charting process

Data charting refers to the creation of data (‘data items’) on the sources selected for inclusion in the scoping literature review. Data charting was conducted independently by the researcher using column headings developed a priori in MS Excel. These are outlined in the next section on data items. A first draft of the results was presented on 31 of July 2023 at the project milestone meeting.

4.1.7 Data items

The column headings developed a priori consisted of the following:

- Geographies: whether the source has a particular focus on specific geographies. Geographies at the country level or above were included. The member nations of the United Kingdom were recorded separately if the source focused on a specific member nation rather than the whole of the UK. The EU was included as a geography where the focus of the article was EU territory as a whole. No changes have been made to reflect the different compositions of the EU prior to and after the UK leaving the EU. A small number of source geographies were coded under Europe where the geographical focus extended beyond the EU to the broader region. Where there was a focus on an individual member state this was coded (in addition to the EU if the source had a substantive focus on both of these geographies). Several other regions (e.g. Africa; Asia; Latin America and the Caribbean) are included as geographies as per the focus of the sources in question.

- Pillar: whether the source relates to the access to information, public participation, and/or access to justice pillars.

- Topic area: what constitutes the primary topic of the source, over and above its engagement with the AC and its pillars.

- Contribution: what, in one sentence, constitutes the principal contribution of the source in relation to the objectives of the scoping literature review.

4.1.8 Synthesis of results

Results of the scoping literature review were synthesised in response to the two research questions and in line with the reporting guidance of the Prisma-SCR guidelines.

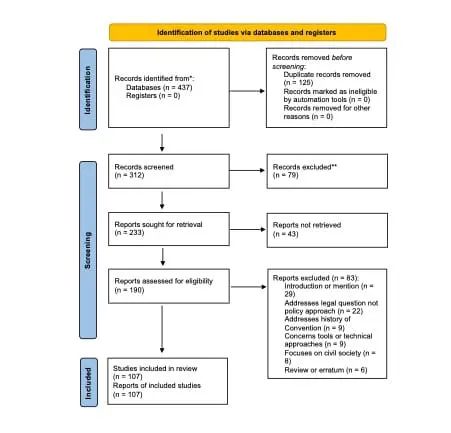

In response to the first research question, the standard Prisma-SCR flow diagram is used to provide an overview of the selection of sources of evidence. A brief note was made on the reason for the exclusion of each source of evidence, and a high-level categorisation of these reasons is provided in the flow diagram.

Data charting was then used to synthesise the characteristics of sources of evidence including source geographies, pillars, and topic area.

In response to the second research question, the synthesis of results provides the outcome of a thematic analysis. This was conducted independently by the researcher subsequent to the initial data charting. The thematic analysis was conducted on the basis of the contributions of each source identified in data charting. As such, the themes are inductively defined categorisations of the ‘type’ of contribution identified in each article.

The contributions of each source are reported under the respective themes in Annex A. Where source contributions were coded under multiple themes, the sources are reported multiple times, i.e. they are reported under each of those themes.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Selection of sources of evidence

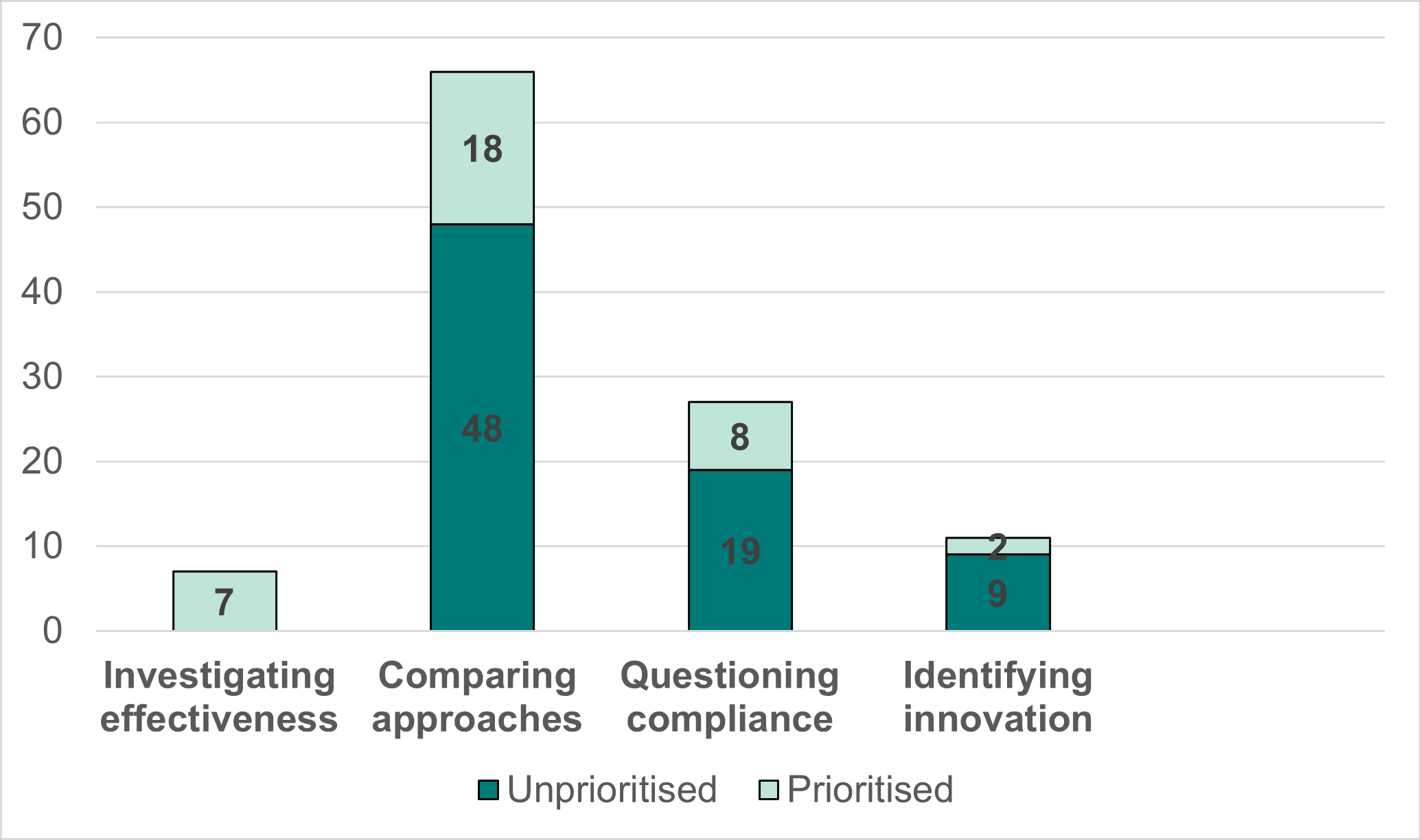

As is visualised in Figure 1, of 312 unique records retrieved, 79 were excluded based on title and abstract, 43 were excluded due to unavailable source content, and 83 were excluded based on source content. As such, 107 sources were included in the review.

Figure 1: Prisma-SCR Flow Diagram.

Source: (Tricco et al. 2018). PRISMA editable flow diagram

4.2.2 Characteristics of sources of evidence

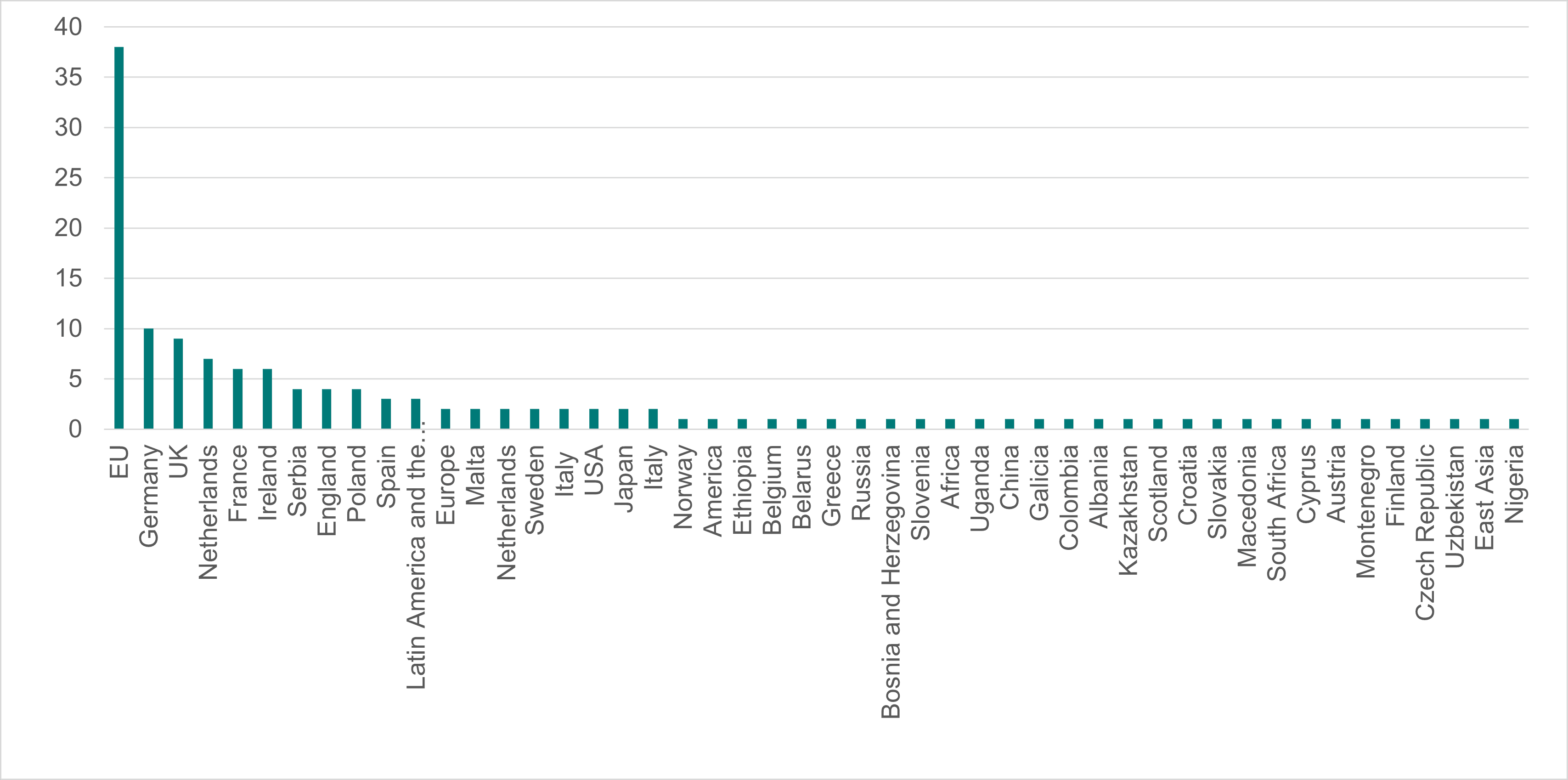

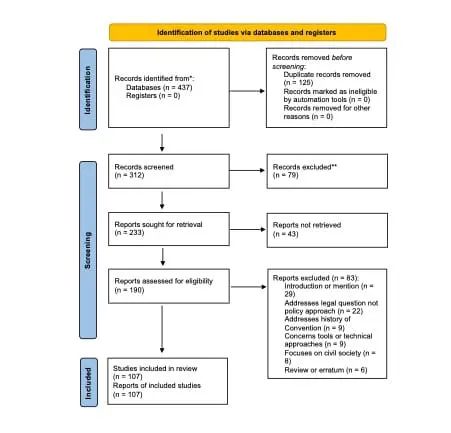

Data on 90 of the 107 sources were entered for geography. The other 17 sources did not have a geography-specific focus.

The geographical focus of the sources is displayed in Table 3 (top 10 geographies) and Figure 2 (all geographies). A clear focus on Europe consistent with the membership of the AC is notable, with a prevalence of discussion of the EU but also widespread discussion of European nation-states.

There is also limited discussion of other regions, often due to comparisons made between the AC and other regional agreements such as the Escazú Agreement (Latin America and the Caribbean), the American Convention on Human Rights (America), or the African Charter on Human’s and Peoples’ Rights (Africa).

A limited number of nation-states that are not members of the AC are also represented, where approaches in other countries have been outlined as comparison. Given the keywords used, these comparisons have made explicit reference to the AC, the Aarhus rights, or the Aarhus regulation. Future research could identify sources on approaches in different countries that do not refer to the AC.

Table 3: Top 10 Article Geographies.

| Geography |

Articles |

| EU |

38 |

| Germany |

10 |

| UK |

9 |

| Netherlands |

7 |

| France |

6 |

| Ireland |

6 |

| Serbia |

4 |

| England |

4 |

| Poland |

4 |

| Spain |

3 |

Figure 2: Article geographies.

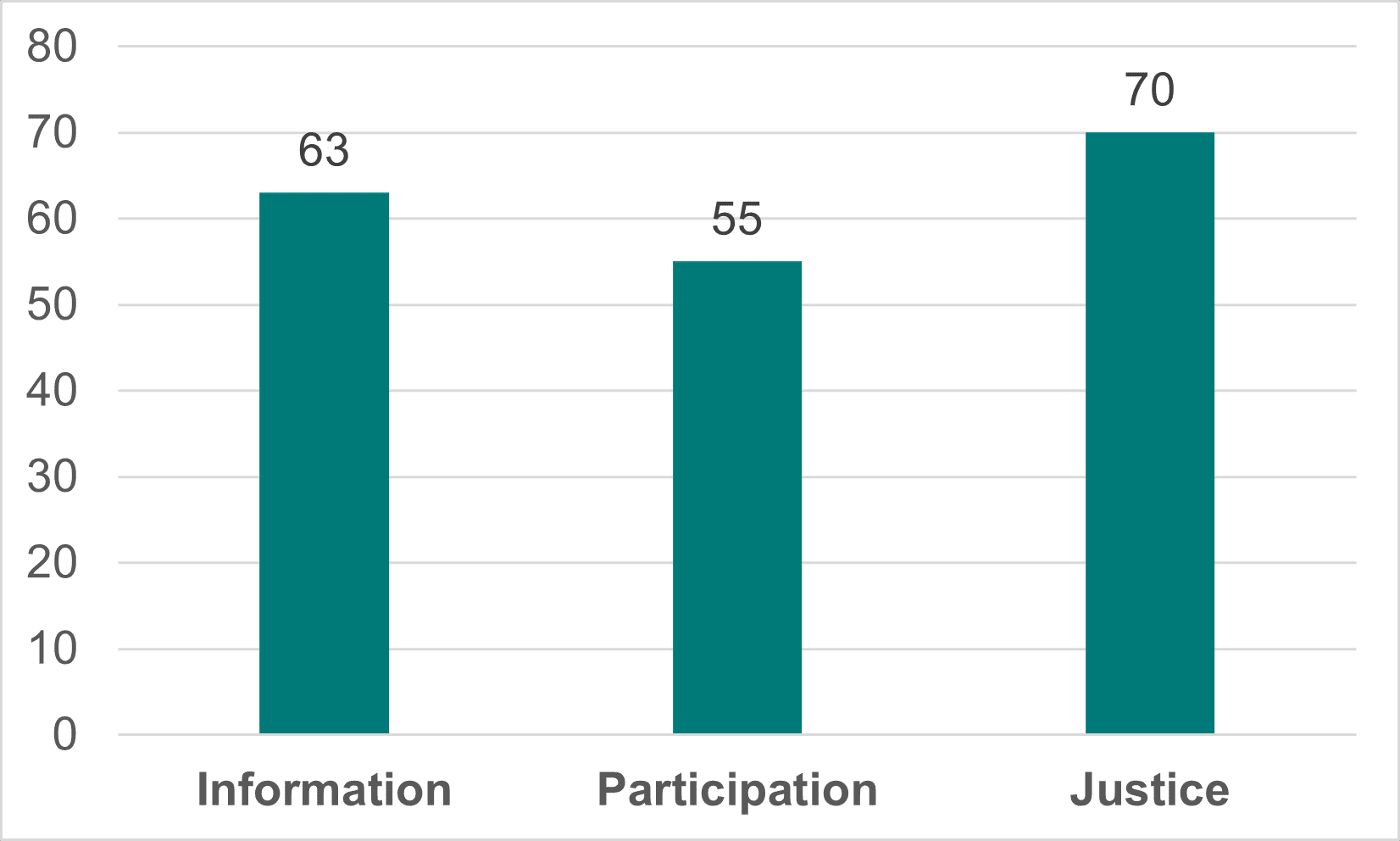

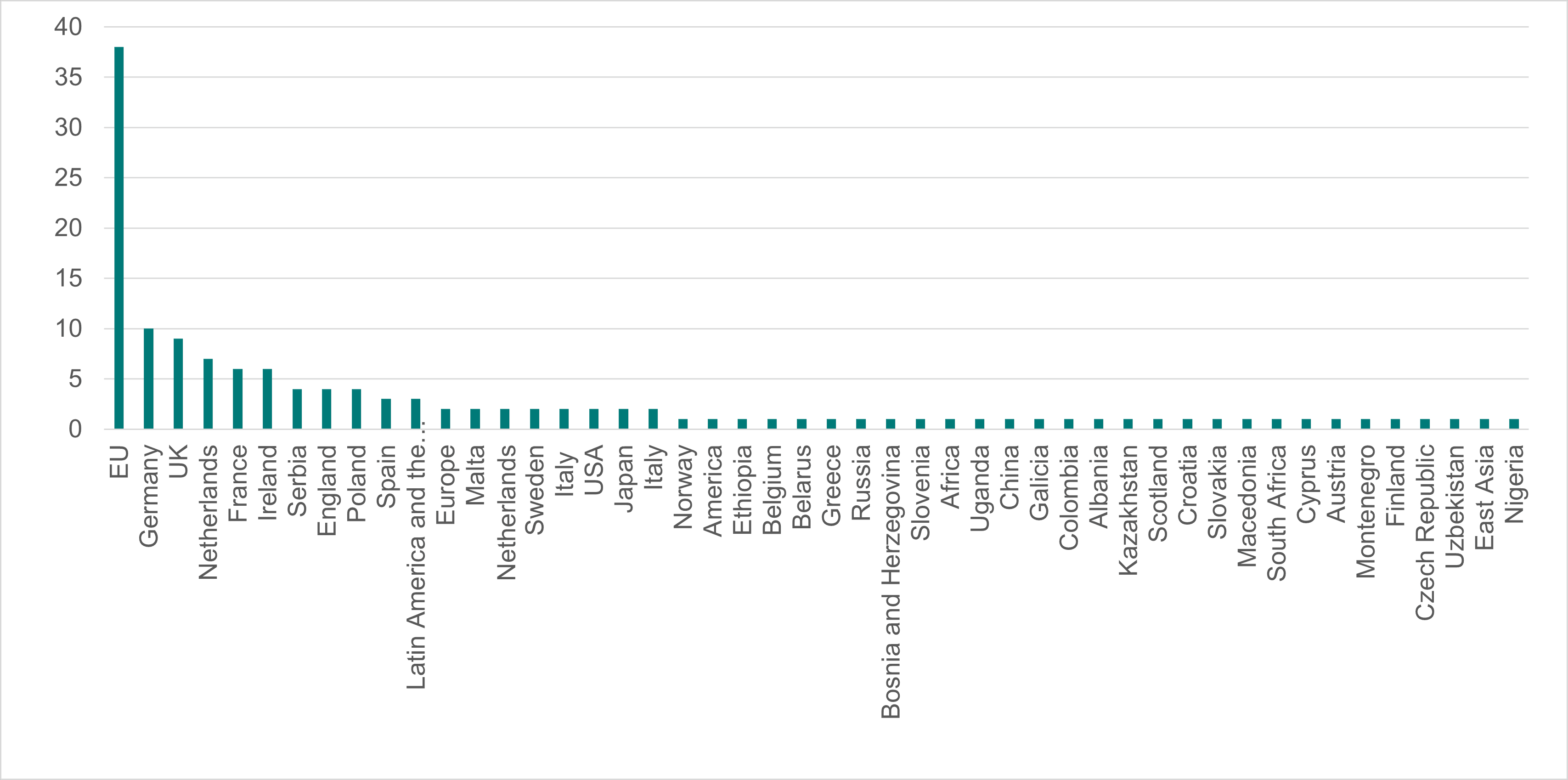

Data on all 107 of the sources were entered for one or more of the pillars (see Figure 3 below). Forty-one of the 107 sources were associated to all three of the pillars, and the remaining 66 were associated to one specific pillar (participation = 14, information = 22, and access to justice = 39).

Figure 3: Article pillars.

Data was entered for topic area on 55 of the 107 sources (see Table 4 below). The data is intended only as an indication of the diversity of different topics discussed rather than a systematic appraisal. Only one topic area was entered for a given source, where a substantive topic over and above the source’s engagement with the AC and its pillars was clearly evident.

Table 4: Article topic areas.

| Topic Area |

Count |

| Human Rights |

5 |

| GMOs |

3 |

| State Aid |

2 |

| Shared environmental information systems (SEIS) |

2 |

| Citizen Sensing |

2 |

| International Agreements |

2 |

| Regional Integration |

1 |

| Park Management |

1 |

| Climate Resilience |

1 |

| Collective Litigation |

1 |

| Pollution |

1 |

| Commercially Sensitive Environmental Information |

1 |

| Climate Change Policy |

1 |

| Disaster Recovery |

1 |

| Multi-Level Governance |

1 |

| E-government |

1 |

| Planning |

1 |

| Energy Policy |

1 |

| Private Bodies |

1 |

| Environmental Defenders |

1 |

| SEVESO III |

1 |

| Environmental Democracy |

1 |

| Trade Unions |

1 |

| Environmental Impact Assessments |

1 |

| Marine Spatial Planning |

1 |

| EPTR |

1 |

| Nuclear Proliferation |

1 |

| Extraterritoriality |

1 |

| Pharmaceuticals |

1 |

| Farming |

1 |

| Plastics |

1 |

| Freedom of Information |

1 |

| Post Emergency Communications |

1 |

| Biodiversity Conservation |

1 |

| Regional Agreements |

1 |

| Bali Guidelines |

1 |

| Right to Water |

1 |

| Hunting |

1 |

| Civil Society |

1 |

| Animal Rights |

1 |

| Technology Regulation |

1 |

| Landscape Planning |

1 |

| Water Governance |

1 |

| Local Government |

1 |

| Marine Conservation Zones |

1 |

4.2.3 Results of individual sources of evidence

The contribution of each source by theme has been included in Annex A.

4.2.4 Synthesis of results

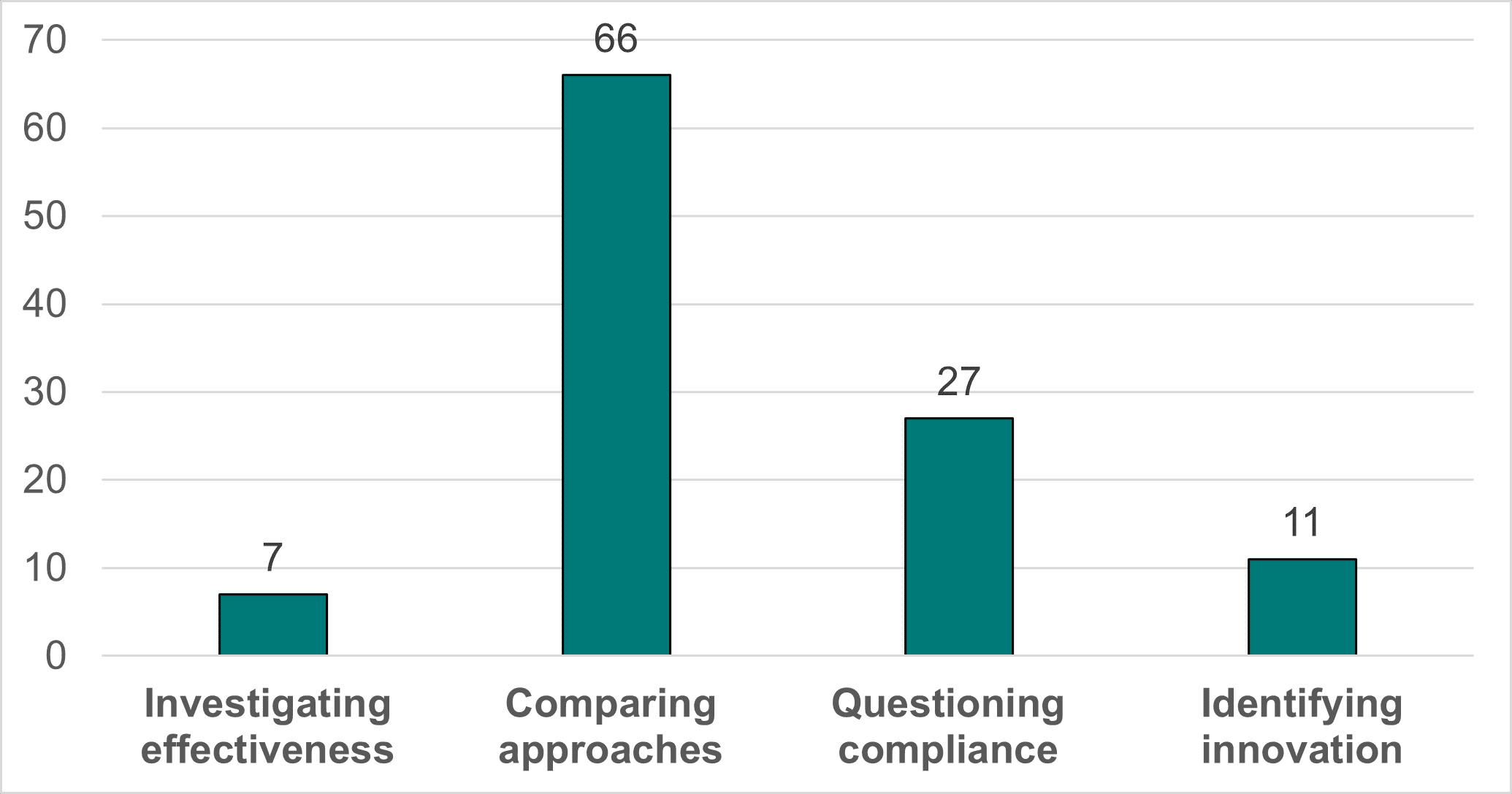

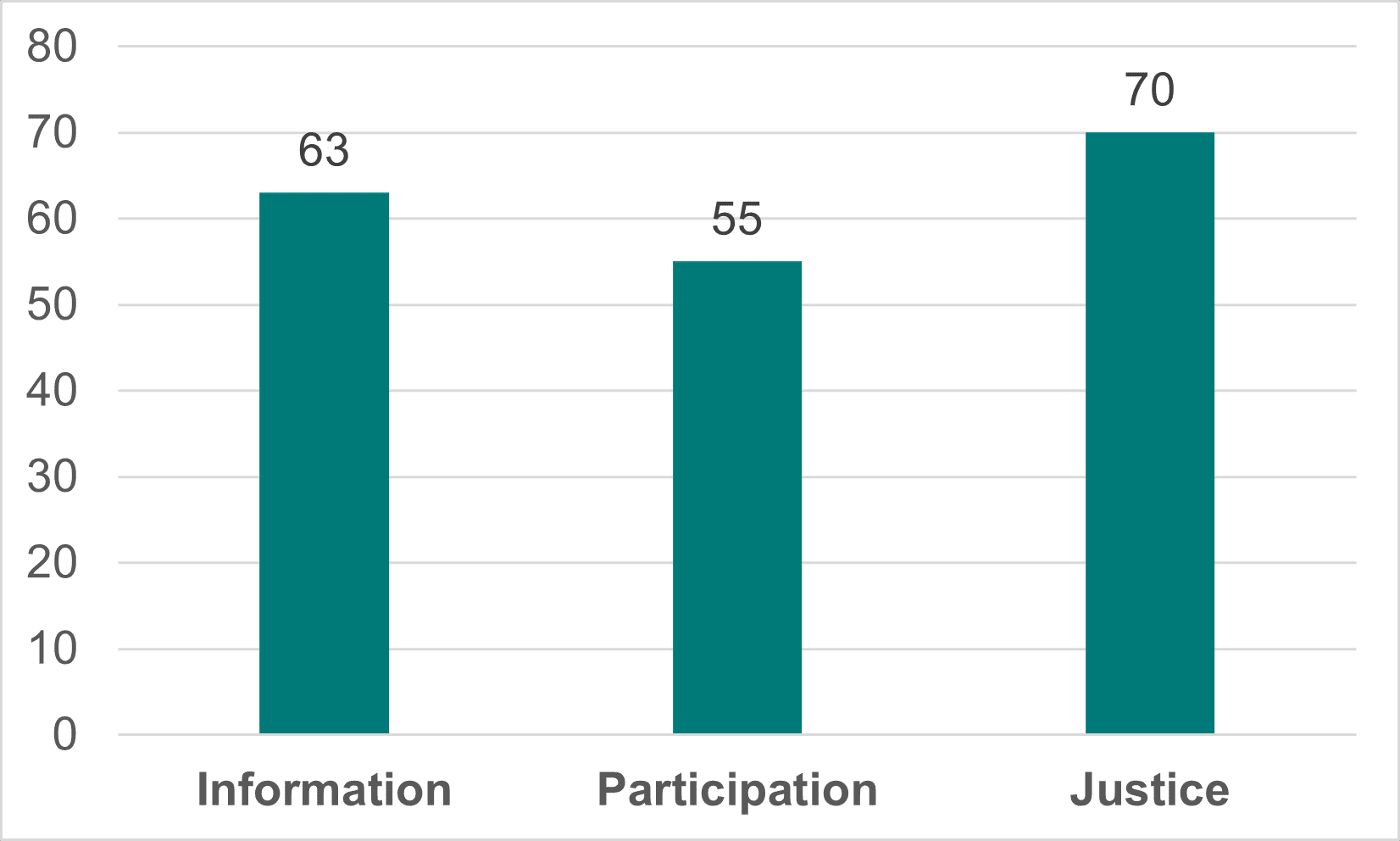

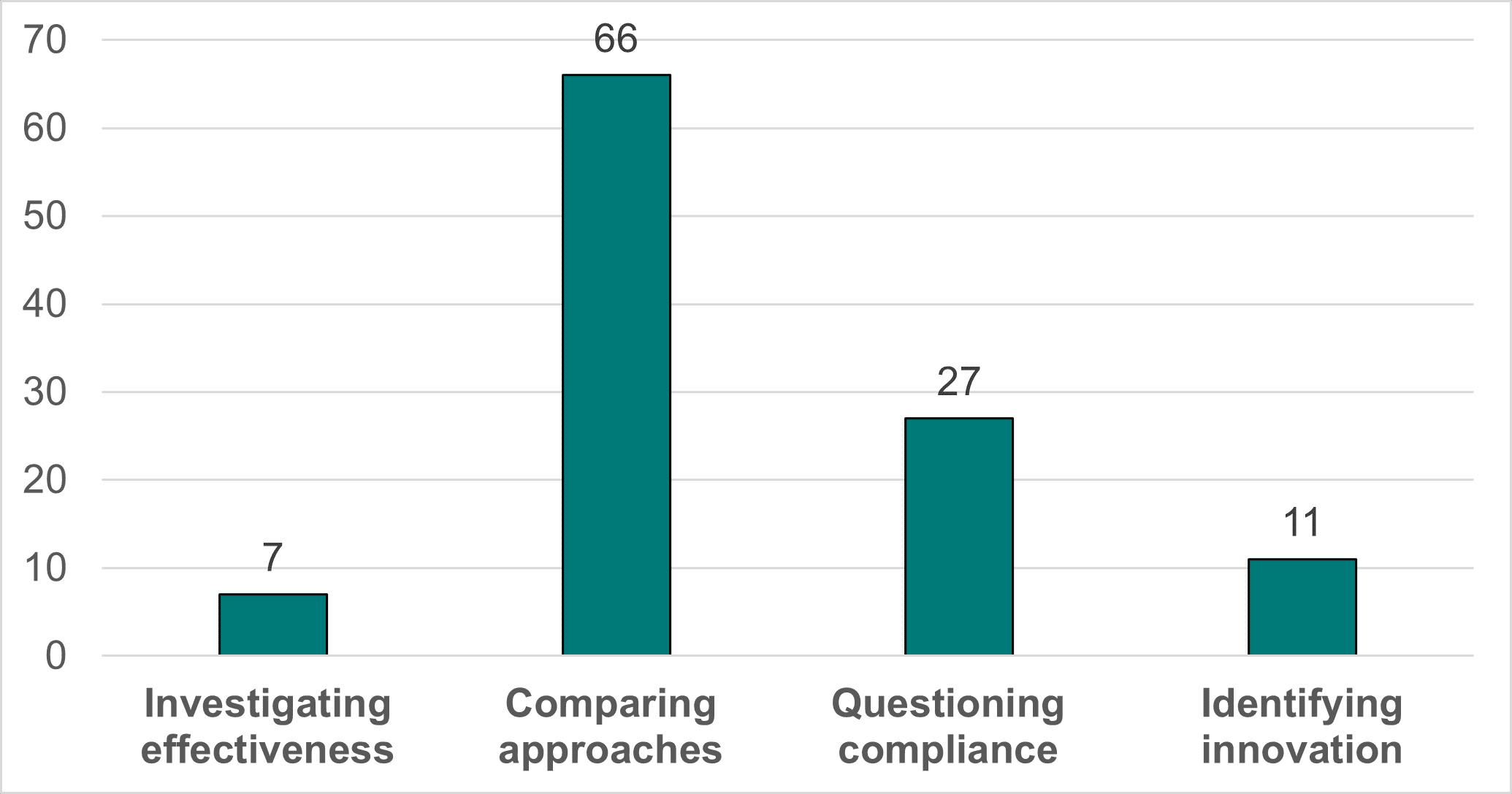

The inductively defined themes are as follows:

- Investigating effectiveness: In some cases, the primary contribution of the source was to investigate the effectiveness of the approaches to compliance outlined. These sources tended to use historical, conceptual, quantitative, and experimental arguments to consider approaches to compliance with the AC in a broader context, situating the AC itself in relation to environmental justice and governance more widely, and encouraging reflection on how to approach implementation of the AC rights.

- Comparing approaches: In most cases, the primary contribution of the source was to facilitate comparison of the approaches to compliance outlined. These sources drew comparisons between agreements as well as between countries and highlighted the importance of understanding particularities seen in specific approaches.

- Questioning compliance: In many cases, the primary contribution of the source was to question whether the approach to compliance outlined was indeed compliant and whether it is aligned with the values and objectives of the AC. While this is similar in some respects to ‘comparing approaches’, the focus on a particular issue in relation to compliance present in these sources was deemed to be a sufficient basis for a distinct theme.

- Identifying innovation: In some cases, the approaches to compliance outlined were prospective, recommended approaches. This was deemed different to ‘comparing approaches’ in view of this.

The sources coded under each theme are shown in Figure 4. A small number of the 107 sources were coded under multiple themes such that a total of 111 source-codes were recorded.

Figure 4: Article themes.

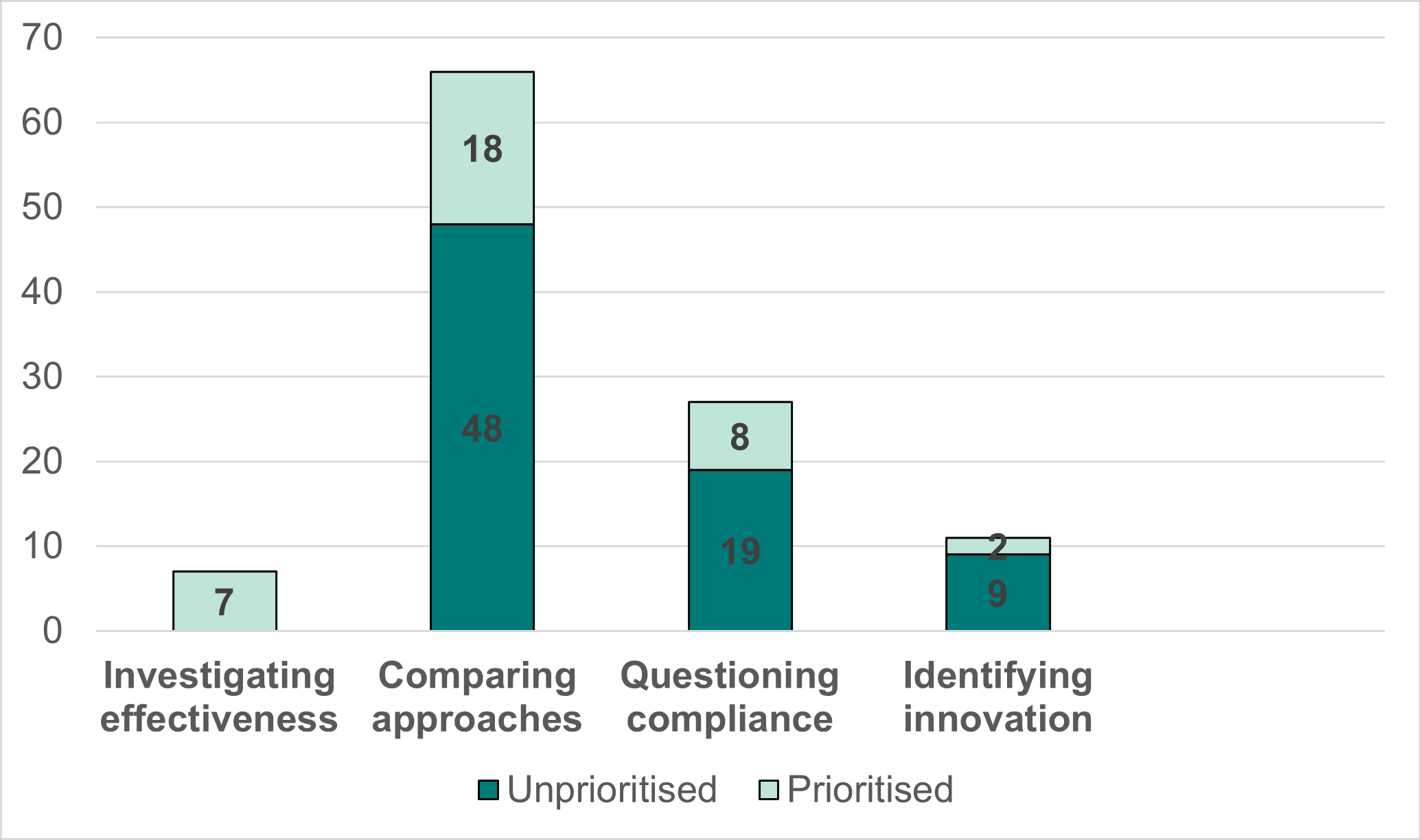

Sources coded under each theme were prioritised for narrative treatment in the summary of evidence section based on a qualitative assessment of their relevance to the objectives of the study. Thirty-five of the 110 source-codes were prioritised, which equated to 31 unique sources. The prioritised sources are visualised in Figure 5. As per the previous section, the contribution of all the sources has been summarised, and this information has been included in Annex A.

Figure 5: Article themes with priority sources.

4.3 Discussion

4.3.1 Summary of evidence

The summary of evidence has been organised by theme and similar sources under each theme have been clustered as appropriate to ease readability.

Investigating effectiveness

The review of effectiveness in (Mason 2014) relies on a historical and documentary analysis of the drivers for the emergence, institutionalisation, and effects of the AC’s information disclosure requirements. Specifically, Mason looks at democratisation and marketisation as such drivers. While he finds both very significant, he argues that “the UNECE’s promotion of political modernization in Central and Eastern Europe has deferred in practice to market liberal norms of governance” (Mason 2014, 84).

Mason’s review of procedural, substantive, and normative effects of national approaches to the AC’s information disclosure requirements finds that there is “a structural imbalance in the articulation of Aarhus rights between social welfare and market liberal perspectives, and that the dominance of the latter has eroded the efficacy of the convention’s information disclosure obligations” (Mason 2014, 85). This argument is informed by the identification of procedural flexibility allowed to implement the AC rights in accordance with national legislative frameworks, a lack of specification of substantive as opposed to procedural environmental rights, and a normative aversion to applying information disclosure obligations to private enterprise.

(Whittaker, Mendel, and Reid 2019) also traces trends in the implementation of information access rights to the historical context for the emergence of the AC, and links this to effectiveness. The broad focus of the paper is how the AC’s conceptualisation of these rights has informed the way in which research on them has been conducted. The study provides a literature review of scholarship on information rights in the UK since the 1980s, and finds two key trends in the research that they argue are derived from the AC’s conceptualisation: a “dominance of research focusing on the disclosure of environmental information through requests over the proactive disclosure of environmental information” and a “focus on the holders of environmental information over the users of the right and the motivations of these users” (Whittaker, Mendel, and Reid 2019, 466).

The authors argue that these trends result in research gaps that undermine the effective guarantee of access to environmental information in the UK. They advocate, therefore, for empirical studies in response to these gaps. Also they support critical engagement with the impacts of the AC’s conceptualisation of rights on their practical implementation as well as the academic discourse concerning this issue.

A series of sources led by Professor Susanne Kingston, an academic and judge in the EU’s General Court, investigate the effectiveness of AC-derived rights and the variable ways in which these have been applied in the domain of nature governance.

(Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022) introduces the development of the ‘Nature Government Index’ (NGI), which codes more than 6,000 international, EU, and national laws to trace the evolution of law relating to nature governance in the EU. At a national level, this focuses on France, the Netherlands, and Ireland; these countries were selected to ensure coverage of countries with different sizes, legal traditions (common and civil), records of compliance with the AC, and time taken to ratify the AC (by 2002, 2004, and 2012 respectively).

The NGI provides “strong empirical confirmation of the democratic turn in European environmental governance, while revealing the significant divergences between legal systems that remain absent express harmonisation of the Aarhus Convention’s principles in EU law” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022, 27).

In a partner article (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022) the authors build on the NGI to develop ‘Nature Governance Effectiveness Indicators’ (NGEIs). This relies on a database developed by the research team of instances in which the nature governance laws have been used by the EU, state, and private or non-state actors between 1992 and 2015, tracked against the 14 indicators developed.

For example, an EU-led NGEI is “[n]umber of Article 258 TFEU Nature infringement proceedings commenced by the European Commission against the Member State”, a state-led NGEI is “[s]tate-led proceedings to enforce EU nature law before national courts” and a private or non-state led NGEI is “[n]umber of decided cases before national courts where a private party seeks to enforce EU nature law” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022: 802).

The research reported in the paper involved regressing the NGEI against the NGI as well as against control variables for Gross National Income (GNI) per capita and urbanisation. The principal findings of the research include that “by strengthening private nature governance laws, States may also in fact improve traditional State enforcement of nature laws on the ground” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022: 809), that “while strengthening private governance laws significantly improved levels of State nature enforcement, strengthening traditional governance laws did not” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022: 810), and that there is a “disconnect between Europe’s revolution in private governance laws on the books, and the use of these laws in practice” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022: 811).

In more recent research, (Kingston and Wang 2023) also highlights the importance of developing empirical evidence on the effectiveness of what they describe as a transition from ‘traditional’ to ‘private’ environmental governance rules. Here, traditional environmental governance rules refer to civil fines, criminal penalties, and the use of incentives while private environmental governance rules refer to rules that encourage private actors, defined as non-state actors, to conduct environmental governance themselves based on their AC-derived rights.

The authors use experimental behavioural research based on a serious game to test hypotheses that a combination of traditional and private rules increases compliance compared to traditional rules alone, and that private rules are more likely to be used when traditional rules are perceived as ineffective. Findings from 300 participants in the serious game are seen to support the first hypothesis but not the second.

This is discussed in relation to the research teams findings in (Kingston et al. 2021), based on around 2000 survey responses and over 150 interviews with farmers, environmental non-governmental organisation (ENGO) representatives and citizens in France, Ireland and the Netherlands. This research found that the impact of the new wave of private environmental governance rules is variable, such that the rules can either “crowd out intrinsic environmental motivation, resulting in less compliance and subverting policy objectives” or “crowd in voluntary pro-environmental activity on the part of not only third parties, but also farmers” (Kingston et al. 2021, S144). The authors found that this variability is dependent on the presence of a “supportive regulatory culture, fostered by the State” (Kingston et al. 2021, S157) and discuss a series of potential measures to develop this informed by the findings in the study.

Looking forward, current Chair of the ACCC Áine Ryall, writing in a personal capacity, provides a commentary on how the AC is responding to ‘tempestuous times’ (Ryall 2023). This notes the pressure placed on AC rights by calls to accelerate decision making in response to drivers including climate and biodiversity crises, the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the war in Ukraine and related energy market impacts.

The commentary focuses on how AC bodies have responded to this pressure and sought to offer greater protection to environmental defenders and combat the erosion of opportunities to speak out on environmental issues. Specific measures discussed include: the establishment of a Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders; the preparation of advice for Ukraine relating to the AC rights during conflict; and the issuance of the Geneva Declaration that acknowledged AC rights were and may have been curtailed as a result of policy responses to Covid-19, affirmed the AC rights remained in effect throughout this time, and noted the importance of alternate means of disseminating environmental information e.g. digitally.

In offering this discussion, the commentary provides opportunities for reflection on effective implementation by individual parties in response to these drivers. Further, it provides an overview of how the ACCC are reviewing the implementation of MoP decisions relating to the compliance of individual parties. It notes that this process has not been a core focus of scholarly attention, and highlights that the associated documentation provides important insights on how to overcome barriers to prompt implementation of AC rights.

Comparing approaches

Several sources situate approaches to compliance with the AC in light of the differences between the AC and other agreements, providing a high-level overview of the way in which the rights are expressed in these. (Peña and Hunter 2020), for example, trace the development of the three rights expressed by the AC in international law with reference to agreements including the Rio Declaration, the AC, the Bali Guidelines, and the Escazú Agreement.

They provide an overview of the approach and provisions of the Escazú Agreement as a basis for comparison with the AC. Highlighted features include the development of a pillar on the rights of environmental human rights defenders, and an obligation for their protection, a “stronger and more direct relationship with human rights law” (Peña and Hunter 2020, 127), and a reference to the guarantee of a substantive right to live in a healthy environment.

In their own comparison of the agreements, (Harris 2021) state that the Escazú Agreement’s guarantee of standing “in the public interest of environmental protection” was not present in the AC and the emergence of a broader interpretation of standing has only been achieved as a result of ACCC efforts (Harris 2021, 288).

The human rights basis of the AC and its similarities, differences and relations to other human rights instruments is also a consistent feature of comparative analysis.

(Slowik 2023) compares the lack of an obligation to guarantee a substantive right to the environment in the AC with the inclusion of such an obligation in the Banjul Charter, the San Salvador Protocol, and the Escazú Agreement.

(Peters 2018) compares procedural environmental rights in the AC and the ECHR and argues that attention is needed to how these “differ considerably in objective, content, and scope” (Peters 2018, 1) in order to move away from a ‘unitary perspective’ and “concretise the doctrine of existing and emerging procedural environmental rights” (Peters 2018, 27). One notable example cited is the intended beneficiaries: while the AC is intended for the public at large, the article notes, the ECHR focuses on those directly affected by human rights violations (see Peters 2018, 26–27).

(Braig, Kutepova, and Vouleli 2022) compare the AC with the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and make a case for the ECtHR to “stop playing second fiddle to Aarhus” (Braig, Kutepova, and Vouleli 2022, 74). For example, it notes possibilities for the ECtHR to extend standing in view of the wide-ranging impacts of environmental damage and the role of NGOs in supporting vulnerable people to safeguard their rights.

Sources also compare how parties to the AC approach the obligation to promote the principles of the AC in the conduct of their own international affairs. (Duyck 2015) reflects on the AC’s requirement in article 3 paragraph 7 that parties “promote the application of the principles of this Convention in international environmental decision-making processes and within the framework of international organizations in matters relating to the environment” (United Nations 1998, 4) and the subsequent agreement of the Almaty Guidelines in 2005, which led to the development of institutional mechanisms in support of this obligation.

Duyck finds that the support of the AC has been focused on developing awareness of the obligation and the associated guidelines and that “the parties tend to favour domestic solutions (such as the inclusion of civil society representatives in governmental delegations) rather than reflect the Aarhus principles in their negotiating positions” (Duyck 2015, 123).

This is based on a comparative review of national implementation reports, which highlights the increasing number of countries that detailed measures undertaken in response to the requirement following guidelines issued in 2010, as well as responses to a survey issued by the AC in 2015. The article also reviews submissions of AC parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and notes the support expressed by AC parties such as the EU, Switzerland and Norway for access to information and participation in the UN climate regime.

A large number of sources provide comparative analysis of how individual parties approach compliance with the three core pillars of the AC. As previously outlined, research led by Susanne Kingston uses quantitative legal research to compare the evolution and effectiveness of the Aarhus rights in the domain of nature governance, with a focus on France, the Netherlands and Ireland (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022; Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022).

In the NGI, what they term ‘inter-jurisdictional normalisation’ is used to enable the quantitative comparison of Aarhus rights in individual jurisdictions. For example, they quantify the strength of ‘Access to Information’ (ATI) in international, European, French, Dutch and Irish law as 30.12, 62.6, 41.45, 82.61, and 46.64 respectively.

The typology developed in the NGI enables detailed comparative metrics that are associated to underlying governance rules. One significant finding they report is that “[w]hereas the NGI Aarhus sub-indices increase largely in lockstep for the five jurisdictions in the case of public participation and access to information, the spread of trajectories is markedly wider for access to justice” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022, 40). This is attributed to the lack of EU-led harmonisation of access to justice provisions, and this in spite of CJEU case law in ‘Slovak Brown Bear’ (2011) intended to strengthen the implementation of these provisions.

The development of the NGEI also enables comparison of the use of these governance rules in different jurisdictions. As such, the NGI records Aarhus rights ‘on the books’ and the NGEIs record use of the Aarhus rights in practice. At a high level, the authors find that “the use of private nature governance mechanisms in practice has not kept pace with their development in law” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022: 814).

They also note that this is compounded by the difficulties they faced compiling information on the use of the Aarhus rules, reflecting “a basic lack of transparency on the success of these new governance mechanisms, a situation itself incongruous with the aims of the Aarhus Convention” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022: 814).

In this context, they discuss the findings in the paper outlined earlier reporting survey and interview data on the attitudes to and use of AC rights in France, the Netherlands, and Ireland among farmers, ENGO representatives and citizens (Kingston et al. 2021). As discussed, the authors found variability in use of the AC rights to be dependent on the presence of a state-led regulatory culture that was supportive. The comparative analysis of the culture in the three countries they present, therefore, represents an analysis of the effectiveness of the AC rights, given the disparities they note between their existence and use.

Other examples of comparative analysis of approaches in different EU member states include (Keller 2020), (Ohler, Peeters, and Eliantonio 2021), (Gieseke 2020), (Jendrośka 2012), and (Bünger and Schomerus 2011).

(Keller 2020) sets out to identify and highlight potential challenges for domestic legal practitioners when applying EU environmental law in different jurisdictions. One example cited is the difference between French and German approaches to standing, in view of the relatively broad standing allowed under the ‘qualified interest’ test in France and the relatively narrow standing allowed in instances where ‘Schutznormtheorie’ (protective norm theory) is applied in Germany.

(Ohler, Peeters, and Eliantonio 2021) review 20 years of the development of Germany’s approach to article 9 paragraph 3, noting that public interest litigation was not traditionally possible in Germany. The authors state that this history has consisted of “adding fragmented amendments which often generated more complexity and legal uncertainty” (Ohler, Peeters, and Eliantonio 2021, 388) and advocate for a simplification and affirmation that ENGOs should consistently have standing.

(Jendrośka 2012) provides a broad overview of the status of the three pillars at EU and member state levels and highlights some issues in implementation. On access to information, for example, the author notes issues derived from the existence of parallel legal regimes in many countries for access to information in general and access to environmental information in particular, including with respect to definitions of information and documents, timeframes for information provision and provisions relating to confidentiality (see Jendrośka 2012, 81).

(Bünger and Schomerus 2011) identify issues with a lack of definition of private bodies in UK and Germany.

As previously outlined, (Mason 2014) compares national approaches to information disclosure as part of an overall argument concerning the role of democratisation and marketisation drivers in the emergence and institutionalisation of the AC.

His overall argument is that AC requirements for information disclosure rely on a market liberal approach, for example by exempting private companies from information disclosure unless they perform the functions of a ‘public authority’, and allowing a discretion to members in how this is determined that enables significant discrepancies (the example he cites is the difference between a restrictive definition in the UK and a broad definition in Ireland).

As such, the examples of national implementation he compares tend to be instances in which parties to the AC have approached information rights in a way that has “minimal market restricting effects” (Mason 2014, 95). One exception is the right to access information directly from private companies enjoyed by the public in Norway. Mason notes that the EU vetoed a Norwegian proposal to extend this right under the AC during discussions on the 2009-14 AC strategic plan.

With respect to the EU, prior to the ACCC finding of non-compliance in 2017 and the subsequent revision to the Aarhus Regulation in 2021, (Squintani and Plambeck 2016) argued that the EU’s approach to plans and programmes was non-compliant with article 9 paragraph 3. They highlight the importance of this given the reliance on a ‘programmatic approach’ by EU institutions as well as member states including the Netherlands and Germany.

(Leonelli 2021) reviews the changes in the revised Aarhus Regulation and highlights the extension of scope of the access to justice provisions to ‘all non-legislative acts’ as the most significant change.

Sources often identify individual countries as comparators for best practice.

(Graver 2017) outlines the Norwegian access to environmental information act and its provision for access to environmental information from private entities.

(Hadjiyianni 2020) highlights approaches to standing in Cyprus to advocate for a move away from restrictive interpretations of standing.

(Danthinne, Eliantonio, and Peeters 2022) outlines how courts in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands have used the generous approach to standing in article 9 paragraph 2 in interpretation of article 9 paragraph 3, which has a broader scope in that it relates to all national laws relating to the environment but is much more vague in relation to standing for ENGOs.

(Ryall 2011) argues that the establishment of a Commissioner for Environmental Information has been a valuable extra-judicial mechanism for Ireland’s delivery of the AC’s rights on access to information, given this has highlighted “deficient administrative practices, poor enforcement and weak judicial control” in Ireland’s delivery of these rights (Ryall 2011, 46)

Questioning compliance

With respect to the UK, sources coded under this theme addressed debates including whether the definition of private bodies in Scotland, England, Wales, and Northern Ireland was sufficient in view of AC access to information provisions (Bünger and Schomerus 2011). Furthermore, whether changes to civil procedure rules on costs for environmental claims in England and Wales were sufficient for compliance with provisions on prohibitive expense (Sarathy 2015; Knibbe 2017), and whether the 2021 Environmental Act was consistent with AC public participation requirements (Lee 2023).

Sources further addressed issues of compliance in view of the systemic nature of the climate crisis and the implications for traditions of legal standing based on the identification of individual litigants.

(Kelleher 2022), for example, “explores whether an exceptional approach to standing rules is needed to square the gatekeeping function of the courts of states/international organisations that are signatories to the Aarhus Convention with the complexity and urgency of the climate crisis” (Kelleher 2022, 107).

She argues that standing rules do not need to be rearticulated but parties to the AC “need to take procedural human rights obligations under the Aarhus Convention seriously” (Kelleher 2022, 107). The article further argues that the CJEU and the Irish Supreme Court have not adopted a sufficiently broad approach to standing in view of the systemic nature of the climate crisis and suggests that Dutch case law in ‘Urgenda’ “could provide a template for standing rules that are suitable for realising the environmental stewardship and accountability purposes of the Aarhus Convention” (Kelleher 2022, 133).

The relationship between the AC and broader human rights obligations also emerged as a prominent concern. (Slowik 2023) claims that the substantive right to “an environment adequate to his or her health and well-being” referenced in the objectives of the AC has not attracted significant attention, and sets out to explore obligations in relation to this substantive right under the AC.

As noted previously, Slowik compares the lack of a specific obligation to guarantee rather than contribute to such a substantive right in the AC with the inclusion of such an obligation in the Banjul Charter, the San Salvador Protocol, and the Escazú Agreement. In view of this, he concludes that the ‘definitional argument’ for such a lack, revolving around the challenges inherent in defining such a right, is not a strong one.

With respect to the status of the right as outlined in the AC, and therefore with implications for approaches to compliance with the AC, Slowik argues that “the substantive human right to the environment is an abstract moral claim which is substantiated by Aarhus’ procedural rights” (Slowik 2023, 206). This argument is informed by the view that rather than a ‘backdrop’ (Barritt 2020) the delivery of the substantive right is a long-term objective of the AC inherently linked to short-term obligations relating to procedural rights (Dellinger 2012).

Finally, (Hadjiyianni 2017) explores regulatory mechanisms to discipline the conduct of EU external actions in line with AC obligations, and queries the abilities of third countries to access justice in view of these. This usefully highlights the importance of the way in which AC obligations extend to the public “without discrimination as to citizenship, nationality or domicile” (United Nations 1998, 5).

Identifying innovation

Two articles led by Anna Berti Suman develop a case for the legal recognition of citizen sensing activity as a fundamental part of approaches to compliance. (Suman 2021) asks “[c]an the Aarhus Convention framework legitimize citizen sensing and form an obligation for the state to listen to the citizen-generated information, when filling environmental information gaps?” (Suman 2021, 36).

In response, Suman argues that the practice of citizen sensing is justified by the AC right to access environmental information, further noting that AC provisions concerning information exhaustiveness and accuracy strengthen this justification in that these are concerns that motivate the practice of citizen sensing.

Suman further argues that legal recognition for citizen sensing activity is needed, and that such recognition may also compel authorities to consider data derived from citizen sensing when information from official sources is not available.

In conjunction with these arguments, Suman states that competent institutions possess the primary duty for the provision of environmental information, such that there is a responsibility for such institutions to consider whether these duties may be better performed with the assistance of citizen sensing activity.

(Suman et al. 2023), building on this work, develops a framework for implementing a “right to contribute information” alongside the “right to obtain information” currently recognised by the AC, with attention to the “legal and governance processes, capacities, and infrastructures” that would be required (Suman et al. 2023, 1).

4.3.2 Limitations

The study limitations identified include those discussed as follows.

Additional review

The study has not benefited from the involvement of one or more additional reviewers to provide a comparison with the original reviewer’s source identification and screening, data charting, thematic analysis, and prioritisation for narrative treatment. In the absence of this, the reviewer repeated these phases.

Specificity of terms

The study may have benefitted from greater specificity concerning the definition of ‘policy approaches to compliance’. The meanings of this term are broad and can be said to include, for example, both the development of legislation and the use of enforcement mechanisms. The term is also not specific about the actors involved.

This said, the broad terminology used had benefits as well as disadvantages. The approach enabled a broad set of results containing a wide range of different insights. There was also a clear and simple relationship to the search queries developed. Limiting the search query to keywords that specifically refer to the AC was deemed appropriate given this terminology, and this resulted in a reasonably targeted set of results.

As discussed in the recommendations section further below, future research could adopt or develop a more advanced typology, potentially with reference to those adopted in the development of the NGI and NGEIs previously discussed (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022; Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022).

Fragmented and incomplete information sources

Irrespective of the specific terms used, the study was challenged by fragmented and incomplete information on policy approaches to compliance with the AC in general.

This is noted in the development of the NGI and NGEIs, the most comprehensive similar efforts identified in the study. The NGI involved efforts by the research team as well as 50 law graduates and students over a five-year period (see Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022, 36).

The information used in the development of the NGEIs derive from a large range of public databases (see Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022, 815) as well as “over 300 formal and informal requests for access to environmental information made to the European Commission and to national and sub-national bodies within Ireland, France and the Netherlands” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022, 800).

Even then, as above, they note how difficult compiling the information was, citing a lack of transparency. Related, they further state that “[w]hile certain information can be found in the Aarhus State Parties’ periodical reports to the Aarhus Convention Secretariat, this information is patchy and is largely confined to reports of legal implementation (law “on the books”)” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022, 797).

Information sources and source eligibility criteria

The information sources used and related source eligibility criteria significantly informed the outcomes. As discussed in the methods section, the decision to limit the review to sources published since 2008 was made to increase the relevance of sources to current and future approaches to compliance, given the ongoing development of relevant legislation and case law. Sources included in languages other than English were excluded due to capacity and available language skills; and the prioritisation of published academic sources reflected the availability of standardised academic databases, and the capacities of these for developing an efficient and rigorous review, rather than a judgment on the relevance of other sources such as legislation, case law, legal communications and/or policy reports.

It is worth noting that the focus on academic sources had benefits as well as disadvantages. In terms of benefits, academic sources included a broad range of analytical and conceptual as well as descriptive information that would arguably not be present in many other source types (e.g. in national implementation reports). Academic sources also included sources from a range of disciplines that would not necessarily be represented in other source types (e.g. in legal databases). In terms of disadvantages, it was challenging to screen academic sources to only include those that displayed a substantive focus on ‘policy approaches to compliance’ given this was often not the primary aim of the source in question.

Academic information sources used

More widely, there are specific limitations relating to the two academic databases used (Scopus and the Web of Science Core Collection). Notably, a focus on journals as opposed to books was evident in the search results. Although many books were included in the search results, several prominent examples were missing (e.g. Barritt 2020)

4.3.3 Recommendations

The study aimed to contribute to the review of Scotland’s implementation of its obligations under the AC, and to demonstrate due regard to developments in international environmental protection legislation when doing so.

While the study objective was to develop an awareness of available academic literature on approaches to compliance with the AC in Scotland and internationally, these recommendations relate to the broader aim. As such, they consider the relevance of both academic and non-academic sources. They also make limited reference to methods that could be used to build on the scoping literature review conducted in this study.

Typologies

Future research may benefit from a more advanced typology to specify and prioritise different types of policy approaches to compliance with the AC. The development of the NGI and NGEIs provides a useful comparison to the study and could be used as a basis for this. These focus on law and practice respectively and intend to capture the approaches of a broad range of actors whether national or sub-national, state or non-state. As such, they can be understood to develop a database of ‘policy approaches to compliance’ that benefits from an advanced and relevant typology worthy of further attention.

By ‘nature governance laws’ or ‘nature governance rules’ (the two are used interchangeably), the NGI research team mean “legal tools or ‘architectures’ used to promote compliance with nature conservation rules” (Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Lima, et al. 2022, 30).[12] This includes ‘all forms of law’ including legislation, case law, and non-binding ‘soft-law’ (e.g. EU ‘Communications’ or ‘Notices’). The laws included are categorised in a typology comprising four sub-indices (3 of which correspond to the AC rights), each with 6-15 variables.

The associated Nature Governance Effectiveness Indicators (NGEIs) sets out to identify instances in which the laws in the NGI are used by a range of bodies including state, non-state, national, and sub-national actors. The researchers also develop a process of ‘inter-jurisdictional normalisation’ to facilitate the comparison of laws across different national legal systems.

The researchers suggest the extension of their approach to other states and other domains of environmental law such as for air water quality (see Kingston, Wang, Alblas, Callaghan, Foulon, Daly, et al. 2022, 812).

Information sources

Future research would benefit from engaging with a wider range of information sources. A list of recommended source types is included below.

Academic sources identified in this study

Many of the sources identified in this study have conducted their own literature reviews and comparative analyses, and these sources and their underlying data, when available, would be beneficial in future research. As previously noted, the development of the NGI and NGEI are significant examples. This research is the outcome of a European Research Council project.

AC national implementation reports

The national implementation reports provide a useful overview of the policy approaches to compliance undertaken by each party to the AC. As above, this information has been described as patchy and incomplete, but it relies on a standardised format and can facilitate comparative analysis.

AC synthesis reports

The AC Secretariat publish a ‘synthesis report’ in response to the national implementation reports for the consideration of the MoP.

EU national and synthesis reports

In-depth national and synthesis reports and information overviews have been undertaken in response to direction by EU bodies and institutions. Several such resources are available at the ‘Convention and the EU’ webpage. Prominent examples include:

The webpage also makes reference to the ‘Commission’s expert group on Aarhus Implementation’. Further information can be found in the minutes and summary reports resulting from this group’s meetings.

ACCC documents

Extensive documentation is provided on each communication made to the ACCC. This is available in the recorded communications from the public. Where a decision has been adopted by the Compliance Committee, the decision is also posted here. UNECE then records all decisions adopted by the MoP.

MoP compliance review process documents

As stated prior, ACCC Chair Áine Ryall notes that “an increasing amount of the Compliance Committee’s time and resources are now devoted to reviewing the implementation of decisions of the Meeting of the Parties (MOP) on individual Parties’ compliance” and that “[t]he Committee’s reports, and progress reviews, on the implementation of MOP decisions provide valuable guidance on what compliance with the Convention’s provisions in practice requires”(Ryall 2023, 164). These resources are available for the most recent MoP in October 2021.

Aarhus Clearing House / Aarhus Centers

The ‘Aarhus Clearing House’ exists to collect information relevant to the AC rights at a national, regional, and global level. ‘Aarhus Centres’ also provide an infrastructure for the review and development of approaches to compliance with the AC. There are 60 such Aarhus Centres, spread across 15 countries. These are clustered in Eastern Europe (Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine), South-eastern Europe (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia), the South Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia), and Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan). The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) provide an introduction to Aarhus Centres.

Civil society actors

As stated previously, there is extensive engagement and analysis with the AC provisions in Scotland and the UK by a broad range of civil society actors, which can be found in a wide range of publications. Some relevant organisations that have made recent representations to the ACCC related to Scotland and/or the UK are included below. As also noted, many of these organisations are members of:

Legal sources

As previously noted, it would be beneficial to engage with legal sources that are not published in academic journals or edited collections, whether in the form of legislation, case law, legal communications, practice notes, blogs, reports, or other outputs. Many of these legal sources are collected in legal databases such as those provided by Lexis+ UK, Practical Law, Westlaw UK, and Hein Online, which also provide proprietary content on the status of the AC.

Keywords and research questions

A more expansive approach could rely on developing keywords and/or specific research questions that relate to the individual rights proposed in the AC or to individual measures that have been used to implement those rights.

Methods

Additional methods could be utilised alongside or instead of the desk-based research undertaken. In the first instance, the study would benefit from broader engagement with stakeholders. Such engagement could have included using additional approaches to the acquisition of information. For example, future research could benefit from engagement through information requests (as seen in the development of the NGI and NGEIs) or surveys (as seen in the development of the 2012 and 2013 synthesis reports on implementation of articles 9.3 and 9.4 of the AC).

More widely, interviews and/or workshops could have helped to provide insight on context in Scotland, established priorities for analysis, and developed recommendations as a result of the research.

[12] The use of the term ‘architectures’ is from (Heyvaert 2018, 31).